Balancing Innovation, Regulation, and Systemic Risk-The Case of Pakistan

Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri

Advocate Supreme Court Pakistan, Barrister, Arbitrator Fellow CIArb, Mediator CEDAR,IMI,CMC,U.S.A. , Master Trainer Mediation CEDAR , Legal Educator, Reformist of Judicial System and Legal Education, White Collar Crime Investigator[i]

Table of Contents

Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. i

1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1

2. Financial Stability Risks …………………………………………………………………………….. 3

2.1 Price Volatility and Wealth Erosion

2.2 Undermining Monetary Policy and “Cryptoization”

2.3 Capital Flight and Systemic Risk

3. Consumer Protection Challenges ………………………………………………………………… 6

3.1 Fraud, Scams, and Ponzi Schemes

3.2 Absence of Investor Safeguards

3.3 Financial Literacy and Custody Risks

4. Illicit Finance and AML/CFT Vulnerabilities ………………………………………………. 8

4.1 Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

4.2 Regulatory Arbitrage and Weak Oversight

5. Comparative Regulatory Responses ……………………………………………………………. 10

5.1 Restrictive Approaches: China and India

5.2 Balanced, Risk-Based Approaches: Japan, Philippines, and EU MiCA

5.3 Legalization with Challenges: Nigeria and El Salvador

6. Pakistan’s Virtual Assets Ordinance, 2025 ………………………………………………….. 13

6.1 Establishment of the Pakistan Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (PVARA)

6.2 Regulatory Design and Themes

6.3 Implementation Challenges and Institutional Overlaps

7. Risk Mapping for Developing Economies …………………………………………………… 16

8. A Pragmatic Blueprint for Phased Legalization ……………………………………………17

9. Comparative Notes and Policy Lessons ……………………………………………………… 19

10. Recommendations …………………………………………………………………………………… 21

11. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23

References…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 25

Abstract

The legalization of virtual currencies presents a paradox for developing economies—promising innovation, financial inclusion, and technological advancement, yet introducing significant risks to financial stability, consumer protection, and anti-money laundering frameworks. This article critically examines the law and policy dimensions of virtual currency legalization through comparative analysis of developing jurisdictions, including El Salvador, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, with a particular focus on Pakistan’s Virtual Assets Ordinance 2025. It identifies systemic vulnerabilities arising from decentralization, price volatility, and weak institutional capacity, and argues for a phased, risk-based regulatory framework aligned with Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards. By integrating legal design with policy safeguards—such as licensing, conduct supervision, and central-bank digital currency pilots—the article proposes a balanced approach enabling innovation while preserving macro-financial stability and public trust.

- Introduction

The global financial landscape is being reshaped by virtual currencies (VCs) such as cryptocurrencies and stablecoins, offering prospects of inclusion, lower remittance costs, and technological advancement. For developing economies, these digital assets appear to provide a pathway toward modernization and participation in the global digital economy. Yet, their legalization without adequate safeguards can undermine financial stability, monetary policy, and consumer protection, while enabling illicit financial flows and regulatory arbitrage.

The decentralization and volatility that define VCs also expose structural weaknesses In developing states—limited supervisory capacity, fragmented financial regulation, and low financial literacy. Experiences in El Salvador, Nigeria, and Bangladesh reveal how premature legalization or poor oversight can transform innovation into instability.

Against this backdrop, Pakistan’s Virtual Assets Ordinance 2025 (VAO 2025) marks a turning point, shifting from prohibition to structured regulation through the Pakistan Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (PVARA). This reform seeks to align national policy with FATF standards, introduce licensing and conduct rules, and explore central-bank digital currency (CBDC) development as a safeguard against “cryptoization.”

This article undertakes a law and policy analysis of the emerging risks and regulatory responses surrounding VC legalization in developing economies, with particular attention to Pakistan’s experience. It argues for a phased, risk-based framework that balances innovation with systemic stability, ensuring that digital transformation advances public interest rather than financial fragility.

2. Financial Stability Risks

2.1. Price Volatility and Wealth Erosion

VCs are notoriously volatile, with Bitcoin’s value surging over 1,000% in 2017 before crashing to 70% of its peak value in early 2018.

In El Salvador, which made Bitcoin legal tender in 2021, this volatility has eroded citizens’ purchasing power and strained public finances, as the government’s Bitcoin reserves lost value .

2.2. Undermining Monetary Policy

Widespread adoption of VCs risks “cryptoization” a shift from domestic currency to crypto-assets, which can dilute central banks’ ability to manage money supply and inflation.

This risk is particularly acute in economies with weak monetary institutions, such as Pakistan, where inflation management is already challenging.

2.3. Capital Flight and Systemic Risks

VCs facilitate rapid cross-border capital movement, threatening currency stability. Large-scale holdings of dollar-denominated stablecoins can disrupt deposit mobilization, curtail credit creation, and create systemic liquidity risks.

Macro-Financial Stability Risks

2.4.Volatility and wealth effects

Extreme price cycles (e.g., 2017–2018 drawdowns) destroy household balance sheets and can spill over into consumption and liquidity stress where crypto penetration is high. “Hype cycles” and thin liquidity amplify price manipulation, flash crashes, and pro-cyclical leverage

2.5.Monetary policy leakage & “cryptoization”

Parallel money systems weaken transmission of interest-rate policy and encourage currency substitution (notably via dollar-denominated stablecoins), impairing bank deposit-taking and credit creation. The uploaded Bangladesh chapter emphasises cryptoization risks and retail stablecoin holdings as a macro-critical channel for developing economies

2.6.Capital flight & external accounts

Friction-free cross-border value transfer enables stealthy outflows in inflationary episodes, intensifying exchange-rate and reserve pressures

3. Consumer Protection Challenges

3.1. Fraud, Scams, and Ponzi Schemes

Cryptocurrency-related scams are rampant in developing economies with low financial literacy. Ponzi schemes such as Hyper Verse and MTFE targeted vulnerable populations across Asia and Africa, luring them with promises of unrealistically high returns. Victims are often left without recourse due to weak enforcement frameworks.

3.2. Absence of Investor Safeguards

Unlike traditional financial products, cryptocurrencies lack deposit insurance or statutory investor protection schemes. Losses from exchange hacks (e.g., Mt. Gox, Coin check) illustrate the risks borne entirely by consumers.

3.3. Financial Literacy Deficit

Developing economies frequently lack robust consumer education programs. Public fear and distrust, fueled by scam-related media reports, further hinder adoption

Consumer-Investor Protection Risks

3.4. Fraud, Ponzi, and platform failure

Low financial literacy plus aggressive online marketing breeds affinity fraud and Ponzi schemes; once funds move on-chain, restitution is rare. The risk catalog from the uploaded risk primer (negligence/key loss; phishing; exchange hacks; uninsurability) remains salien.

3.5.Custody & operational risk

Exchange/custodian collapses (e.g., Mt. Gox) exposed weak segregation of client assets, inadequate cybersecurity, and poor governance—risks more acute where supervisory capacity is limited.

4. Illicit Finance and AML/CFT Risks

4.1 Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

The pseudonymous nature of blockchain transactions enables laundering, terrorist financing, and ransomware payments. Colombian law enforcement, for example, has reported cryptocurrency use by drug cartels to move proceeds across borders .

4.2. Regulatory Arbitrage

Developing economies often lack capacity to implement FATF Recommendation 15 fully, creating opportunities for illicit actors. Bangladesh, despite an informal ban, is among the top 15 adopters of virtual assets, largely through unregulated channels, posing significant AML risks.

4.3. Illicit Finance & AML/CFT

4.4. Pseudonymity and typologies

Pseudonymous rails, mixing services, and jurisdictional arbitrage complicate ML/TF controls; VASPs often operate cross-border without consistent KYC, enabling placement-layering-integration at industrial scale.

4.5. Stablecoins and sanctions evasion

Illicit transaction volumes have shifted materially toward stablecoins, magnifying surveillance challenges where chain-analytics capacity is thin.

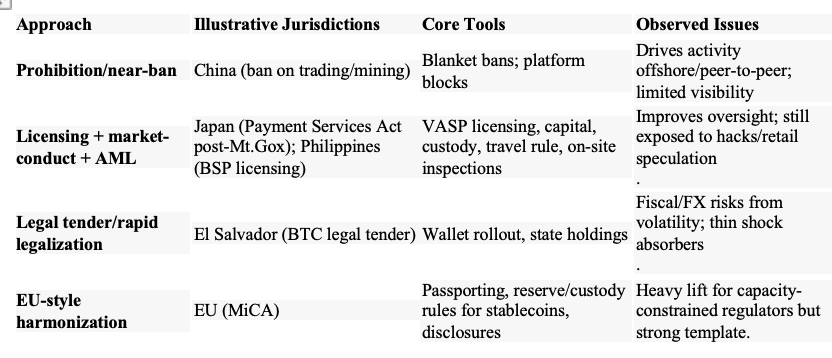

5. Comparative Regulatory Responses

5.1. Restrictive Approaches

China has imposed a comprehensive ban on cryptocurrency trading and mining to prevent financial instability and capital flight. India has oscillated between bans and proposals for regulation, with the Reserve Bank of India warning against systemic risks.

5.2. Balanced, Risk-Based Approaches

The Philippines licenses virtual asset service providers (VASPs) and mandates AML/KYC compliance . The EU’s MiCA regulation provides a harmonized framework covering stablecoins and crypto-asset service providers, serving as a global model.

5.3. Legalization with Challenges

Nigeria initially banned banks from dealing with VCs but later shifted to a regulatory framework to capture remittance flows and reduce illicit activity . However, enforcement and compliance gaps remain.

5.4. Comparative Regulatory Responses

6. Pakistan’s Turning Point: The Virtual Assets Ordinance, 2025

Legal pivot. Pakistan promulgated the Virtual Assets Ordinance, 2025, effective July 8, 2025, establishing the Pakistan Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (PVARA) to license and supervise VASPs, set conduct rules, and align with international standards. Early commentary confirms no retrospective application and clarifies the status of past private crypto dealings (no enforceable legal rights absent compliance). Trade coverage notes entry-into-force and scope, while public posts report PVARA’s outreach to global exchanges via EoIs in Sept 2025.

Central bank stance & CBDC. Prior to VAO 2025, SBP maintained a prohibition on regulated entities dealing in crypto (2018 circular reiterated in May 30, 2025 press note). In parallel, SBP signaled a CBDC pilot to preserve monetary control while enabling digital rails

6.2. Regulatory design themes (from ordinance materials and commentary):

- Licensing & perimeter: VASP categories; fit-and-proper; governance; local presence.

- Prudential & custody: Client asset segregation; minimum capital; cyber/operational risk.

- Disclosure & market conduct: White-paper & marketing rules; suitability for retail; conflicts.

- AML/CFT: FATF travel rule; risk-based KYC; sanctions screening; record-keeping.

- Supervisory toolbox: On-site/off-site inspection; enforcement; cooperation with SECP/SBP; possible regulatory sandbox.

(See official and near-official materials and press/think-tank summaries.)

Alignment with Shariah-compliant products, channeling innovation into supervised rails, and using CBDC as a safer public alternative to unregulated crypto.

6.3. Immediate tensions to manage:

- Dual-mandate friction (innovation vs. prudential safety) in an inflation-prone, FX-constrained economy;

- Institutional overlap (PVARA–SECP–SBP) and clear assignment of prudential vs. conduct vs. payments oversight;

- Capacity gaps (chain analytics, cyber supervision);

- Public expectations vs. phased onboarding (given prior bans and hype cycles).

6.4. Pakistan’s Regulatory Landscape

Pakistan currently has no comprehensive legal framework governing VCs. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) issued a circular in 2018 prohibiting banks and financial institutions from dealing with cryptocurrencies. Nevertheless, informal crypto trading persists, particularly for remittances and hedging against rupee depreciation.

Key challenges for Pakistan include:

- AML/CFT Compliance: Pakistan has been on the FATF grey list in the past and must ensure robust monitoring of VASPs to maintain international credibility.

- Consumer Protection: Absence of clear redress mechanisms leaves users exposed to fraud.

- Fiscal Policy Implications: Crypto adoption could further erode the tax base due to the opacity of transactions.

A phased regulatory approach-starting with VASP registration, AML compliance, and sandbox experimentation-could allow Pakistan to harness benefits while mitigating risks.

7. Risk Map for Developing Economies (and Pakistan) Post-Legalization

- Macro-financial: volatility shocks, cryptoization of deposits/payments, sudden-stop outflows via stablecoins and exchanges

- Prudential: runs on stablecoin-like instruments; VASP failure with client-asset shortfalls

- Conduct/consumer: retail mis-selling, leverage-induced losses, key-loss and phishing, uninsurability.

- AML/CFT & sanctions: cross-border typologies; mixers; insufficient travel-rule compliance.

- Fiscal/tax: base erosion, valuation/reporting arbitrage in lightly supervised markets

8. What Works: A Pragmatic Blueprint (Phased, Risk-Based)

8.1. Phase I – Contain & map risk (first 6–12 months):

- Licensing moratorium + controlled whitelisting of a small number of exchanges/custodians meeting capital, custody, cyber, and transparency standards.

- Mandatory segregation of client assets; daily reconciliations; bankruptcy-remote trust accounts.

- Travel-rule compliance; inter-VASP data standards; sanctions screening.

- Market-conduct guardrails: retail suitability, leverage caps, fair-marketing rules, cooling-off periods.

- Data room: incident reporting; granular on-chain/off-chain data to the supervisor; third-party audits.

8.2. Phase II – Deepen supervision & consumer protections:

- Compensation scheme “lite” for custodial failure funded by VASP levies; standardized disclosure key facts for tokens/platforms.

- Chain-analytics & cyber exercises (table-tops, red-team) across PVARA/SECP/SBP.

- Tax clarity: capital gains rules; information reporting (VASP 1099-equivalent); withholding on certain flows.

- Sandbox only for use-cases with demonstrable consumer and real-economy benefit (e.g., compliant tokenized sukuk, programmable remittance rails).

8.3. Phase III – Systemic safeguards:

- Stablecoin regime (reserve quality, redemption rights, liquidity, daily attestation, independent audits; concentration limits).

- Inter-agency MoUs clarifying who does what (prudential vs. conduct vs. payments vs. AML).

- Cross-border gateways: recognition/“de-recognition” criteria for foreign VASPs; data-sharing with primary supervisors.

- CBDC pilot-to-production path to offer a safe digital money anchor and reduce cryptoization risk (consistent with SBP statements).

9. Comparative Notes for Policymakers

- Japan: licensing + inspections improved hygiene but could not eliminate exchange hacks; custody and governance standards must continually ratchet up.

- Philippines: BSP licensing and AML controls enabled inclusion use-cases but still requires vigilant enforcement capacity.

- EU (MiCA): comprehensive, but resource-intensive—offers a template for stablecoin reserves, disclosures, and passporting that PVARA can adapt in proportion to capacity.

10. Recommendations

10.1. Phased Legalization with Licensing: Introduce a licensing regime for exchanges and custodians, similar to Japan’s Payment Services Act amendments.

10.2. AML/CFT Alignment: Fully implement FATF Recommendation 15 and integrate blockchain forensics to monitor suspicious transactions.

10.3. Consumer Protection Measures: Establish mandatory disclosures, dispute resolution mechanisms, and education campaigns.

10.4. Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) Exploration: To counter “cryptoization,” SBP should accelerate its CBDC pilot programs to offer a state-backed digital alternative.

10.5. International Cooperation: Engage with regional partners and global standard setters (BIS, IMF, FATF) for harmonized regulation.

11. Conclusion

The legalization of virtual currencies presents a defining challenge for developing economies—where the pursuit of innovation must be reconciled with the imperatives of financial stability and regulatory control. While digital assets promise inclusion, efficiency, and modernization, their unregulated proliferation risks amplifying economic volatility, facilitating illicit finance, and undermining institutional credibility.

Pakistan’s Virtual Assets Ordinance 2025 (VAO 2025) demonstrates an important policy shift from prohibition to structured governance. Its framework for licensing, prudential oversight, and FATF-aligned compliance represents a foundation for responsible innovation. Yet, the success of this transition will depend on institutional capacity, inter-agency coordination, and the integration of technology-driven supervision.

A phased and risk-based regulatory approach—anchored in consumer protection, financial literacy, and central bank oversight—offers the most sustainable path forward. By combining legal clarity with policy prudence, Pakistan and other developing economies can harness the transformative potential of digital finance without compromising systemic integrity.

Ultimately, the question is not whether to legalize virtual currencies, but how to do so wisely—through frameworks that balance innovation with accountability, and progress with protection. The lessons drawn from comparative experiences affirm that effective regulation is not a barrier to innovation, but its necessary precondition.

References

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers (Paris, FATF 2021).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), Regulating the Crypto Ecosystem: The Case of Stablecoins and Arrangements (IMF Policy Paper, 2022).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), All That Glitters Is Not Gold: The High Cost of Leaving Cryptocurrencies Unregulated (UNCTAD Policy Brief No 100, 2022).

- Sangita Gazi, The Emerging Risks of Virtual Assets in Developing Countries: The Case of Bangladesh (Preprint, 2024).

- G Ihagh, ‘11 Major Risks Associated with Cryptocurrencies’ (2021) Journal of Emerging Financial Risks 4(2) 67–84.

- Nathaniel Popper, Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent Money (HarperCollins 2015).

- PwC Cyprus, Cryptocurrency Funds: Risks and Opportunities for Investors (PwC Report, 2023).

- State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Circular No. 03 of 2018: Prohibition of Virtual Currency Transactions (SBP 2018).

- Government of Pakistan, Virtual Assets Ordinance 2025 (Gazette of Pakistan, 8 July 2025).

- European Union, Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) (Regulation (EU) 2023/1114, 9 June 2023).

- Central Bank of the Philippines (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas), Guidelines for Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) (Circular No. 1108, 2021).

- Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri, ‘Analysis of the Virtual Assets Ordinance 2025: Pakistan’s Entry into Regulated Digital Finance’ (LinkedIn Post, 2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/zafar-kalanauri-0728539_analysis-virtual-assets-ordinance-2025-activity-7353887152386064384 accessed 10 October 2025.

- Financial Stability Board (FSB), Global Regulatory Framework for Crypto-Asset Activities (FSB Policy Document, 2023).

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS), CBDCs: Opportunities for the Monetary System (BIS Annual Report, 2022).

- Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri, The Double-Edged Sword: Unpacking the Emerging Risks of Virtual Currency Legalization in Developing Economies (2025).

[i] Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri

Advocate Supreme Court Pakistan, Barrister, Arbitrator Fellow CIArb, Mediator CEDAR,IMI,CMC,U.S.A. , Master Trainer Mediation CEDAR , Legal Educator, Reformist of Judicial System and Legal Education, White Collar Crime Investigator

Cell: +92300-4511823; E-mail: kalanauri@gmail.com ; Website: http://www.kalanauri.com ; http://www.facebook.com/people/zafar-kalanauri/100000926160361; https://www.linkedin.com/in/zafar-kalanauri-0728539/; https://www.youtube.com/@kahosunotv