Comparative Lessons from China’s Arbitration Law, UNCITRAL Model Law, and Singapore Convention

Cross-Border Construction Disputes and Beltway/BRI Investments

Comparative Lessons from China’s Arbitration Law, UNCITRAL Model Law, and Singapore Convention

Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri,

Advocate Supreme Court Pakistan, Arbitrator (Fellow CIArb), Barrister, Mediator (CEDAR, IMI, CMC, USA), Master Trainer in Mediation (CEDAR), Legal Educator, Reformist of Judicial System and Legal Education, White-Collar Crime Investigator

Table of Contents

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Abstract

- 3. Comparative Legal Framework

- 4. Challenges in Cross-Border Construction Disputes

- 5. UNCITRAL Model Law and Harmonization

- 6. Singapore Convention on Mediation

- 7. Policy and Practice Recommendations

- 8. Comparative Table of Regional ADR Frameworks

- 9. Model Multi-Tier Clause

- 10. Conclusion

- 11. References

Executive Summary

This article explores the evolving landscape of cross-border construction dispute resolution in the context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Pakistan’s Beltway projects.

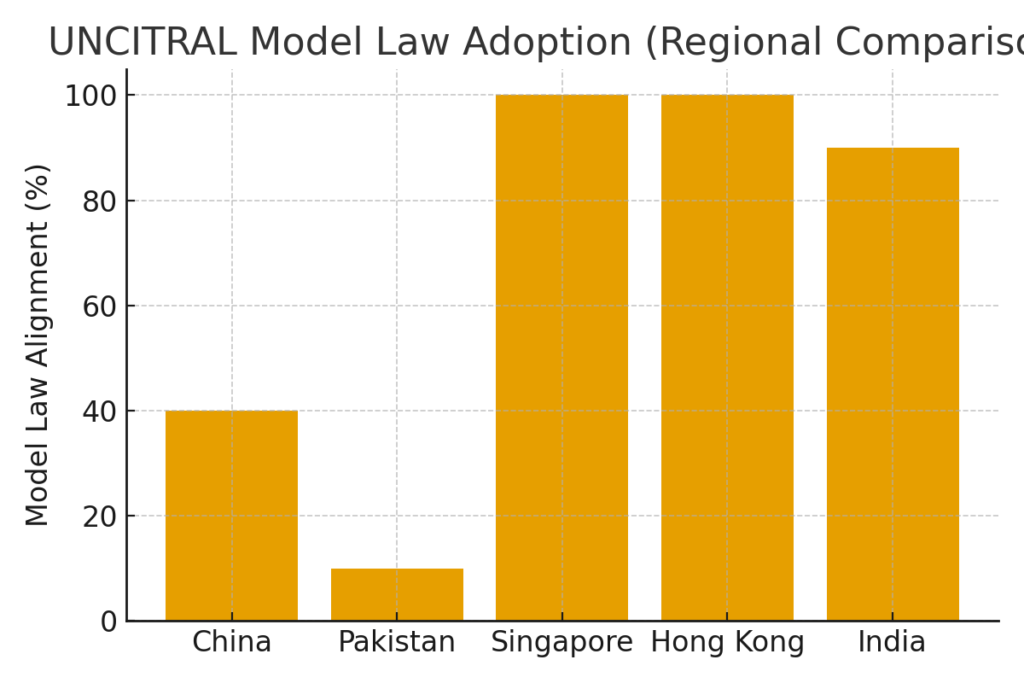

It evaluates China’s Arbitration Law, contrasts it with Pakistan’s outdated Arbitration Act 1940, and examines regional models such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and India that have successfully adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law.

The paper highlights key challenges-including limited recognition of ad hoc arbitration in China, enforcement delays, judicial inconsistencies, and the lack of harmonization in Pakistan’s legal framework-which collectively undermine investor confidence and increase project risk.

To address these issues, the article recommends modernization of Pakistan’s arbitration laws, ratification of the Singapore Convention, creation of an international arbitration and mediation center, adoption of model multi-tier clauses, and international-standard training for mediators and arbitrators.

Figure 1: UNCITRAL Model Law Adoption in Regional Jurisdictions

Abstract

Arbitration and other forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) have become indispensable for resolving disputes in today’s interconnected global economy, where predictability, fairness, and enforceability are critical to sustaining trade and investment flows. China, as the world’s second-largest economy and a leading recipient of foreign investment, has taken significant steps to modernize its arbitration law and strengthen ADR mechanisms, yet challenges remain in areas such as ad hoc arbitration, enforcement delays, and judicial consistency.

Construction disputes-particularly those arising from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Pakistan’s Beltway projects-are uniquely complex, often involving multi-tiered contracts, cross-border parties, state entities, and international financiers. This article critically examines China’s Arbitration Law, compares it with best practices in Singapore, Hong Kong, and the UK, and proposes a regional construction-focused framework based on the UNCITRAL Model Law and the Singapore Convention on Mediation. It calls for collaboration among governments, chambers of commerce, financiers, legal associations, and academia to build robust, neutral, and enforceable dispute resolution systems that enhance investor confidence and ensure the timely, cost-effective completion of mega-infrastructure projects.

I. China’s Legal Framework for Arbitration and ADR

China’s journey toward a modern arbitration regime began with the enactment of its Arbitration Law in 1994, which laid a solid foundation for the country’s dispute resolution framework. The law firmly established institutional arbitration as the primary mechanism for resolving disputes, requiring parties to enter into a written agreement to submit their disputes to arbitration. Its scope is broad, covering contractual and property disputes between parties of equal legal standing, whether they are individuals, legal persons, or organizations.

Under this law, arbitration must be conducted through recognized commissions such as CIETAC, BAC, or SCIA, ensuring consistency and administrative oversight. Arbitral awards issued under these institutions are final and binding, and parties may seek enforcement through the People’s Courts if needed. Judicial intervention is deliberately limited: courts can only set aside awards on procedural grounds, with the Supreme People’s Court retaining the final authority to refuse enforcement of foreign-related awards.

China’s dispute resolution landscape extends beyond arbitration. It incorporates people’s mediation, labor dispute arbitration, and an innovative med-arb mechanism, allowing arbitrators to serve as mediators within the same case-an approach that reflects China’s preference for amicable settlement.

This framework offers several strengths. The “single and final award” mechanism ensures speed and efficiency, helping parties achieve resolution without prolonged appeals. The confidential nature of arbitration proceedings safeguards commercial secrets, an essential factor in high-value disputes. As a signatory to the New York Convention, China ensures that arbitral awards are enforceable internationally, making it a viable venue for global commerce. Finally, the widespread use of mediator-facilitated settlements has significantly reduced court backlogs and encouraged more collaborative, less adversarial outcomes.

Challenges and Critique

Despite progress, several systemic challenges remain:

1. Over-Reliance on Institutional Arbitration

China’s law largely excludes ad hoc arbitration, limiting party autonomy compared to jurisdictions like Hong Kong (UNCITRAL Model Law) and Singapore (International Arbitration Act) where parties enjoy greater flexibility to design procedures

2. Enforcement Difficulties

While China is a New York Convention signatory, enforcement of foreign awards can be delayed due to local protectionism, protracted judicial review, or refusal on vague “public policy” grounds.

3. Judicial Involvement and Inconsistencies

Although judicial review is limited, inconsistencies in local court interpretation sometimes undermine confidence. The reporting mechanism requiring lower courts to consult higher courts before refusing enforcement of foreign-related awards is a safeguard, but it can delay resolution.

4. Party Autonomy and Third-Party Joinder

China’s institutional model restricts parties’ ability to consolidate proceedings or join third parties not bound by the arbitration clause-an increasingly common need in multi-contract and multi-party disputes.

5. Limited Recognition of Ad Hoc Awards

Unlike Singapore, which actively promotes ad hoc arbitration under the UNCITRAL Rules, China has only cautiously piloted ad hoc arbitration in Free Trade Zones, limiting its broader acceptance.

Comparative Perspectives

Singapore

Singapore’s pro-arbitration judiciary, flexible ad hoc framework, and support for international commercial courts make it a global hub for dispute resolution. The Singapore Convention on Mediation, which China has signed but not ratified, is another step toward enforceable mediated settlements.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s Arbitration Ordinance fully incorporates the UNCITRAL Model Law, offers strong confidentiality protections, and allows broad party autonomy. Courts are famously “pro-enforcement,” with minimal intervention except where absolutely necessary.

United Kingdom

The UK Arbitration Act 1996 provides a balance between party autonomy and judicial support, allowing challenges on points of law only in limited circumstances, which enhances predictability while upholding fairness.

Recommendations for Reform

- Formalize Ad Hoc Arbitration – Provide statutory recognition for ad hoc arbitration, especially for international commercial disputes, aligning with UNCITRAL standards.

- Ratify the Singapore Convention – This would enhance the enforceability of mediated settlements and promote mediation as a primary ADR tool.

- Strengthen Judicial Training – Uniform application of arbitration law across provinces would reduce inconsistency and delay in enforcement.

- Promote Transparency – Publish anonymized awards and key judicial decisions to develop persuasive precedent and improve predictability.

- Expand Multi-Party and Multi-Contract Arbitration Rules – Facilitate joinder and consolidation to handle complex commercial disputes efficiently.

- Encourage Technology Use – Develop online arbitration and ODR platforms for cross-border disputes, enhancing accessibility and efficiency.

II. Policy and Practice Recommendations for Beltway Project Dispute Resolution

1. Agreement Drafting and ADR Clauses

To minimize disputes and avoid lengthy litigation, contract drafters should adopt internationally recognized ADR-friendly clauses.

Key Elements of Recommended Clauses

- Multi-tier Dispute Resolution Clause:

- Tier 1: Amicable settlement and negotiation between senior executives.

- Tier 2: Mediation using an accredited mediator or a recognized institutional framework (e.g., CIETAC, ICC, PCA).

- Tier 3: Final and binding arbitration, preferably under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules.

- Choice of Law: Explicitly state governing law (Pakistani law, or a neutral international law such as English law for cross-border finance contracts).

- Language of Arbitration: English or bilingual (English + Mandarin/Urdu, depending on parties’ needs).

- Seat of Arbitration:

- Recommend a neutral, arbitration-friendly jurisdiction like Singapore, Hong Kong, or London for investor confidence.

- Alternatively, designate Islamabad or Karachi as the seat but align procedural rules with UNCITRAL Model Law to ensure neutrality and enforceability.

- Institutional vs. Ad Hoc Arbitration:

- Prefer institutional arbitration under ICC, SIAC, HKIAC, or CIETAC for predictability, transparent procedures, and administrative support.

- Ad hoc arbitration may be used under UNCITRAL Rules if parties want greater control but should include an appointing authority (e.g., PCA or CIArb).

2. Development of ADR Forums and Centers

Pakistan should invest in specialized dispute resolution forums to cater to large-scale infrastructure disputes:

- Pakistan International Arbitration and Mediation Center (PIAMC):

Establish a flagship national center in Islamabad, with regional hubs in Lahore and Karachi, modeled on Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) and Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC). - Integration with Belt & Road Dispute Resolution Mechanisms:

Align Pakistan’s forums with China’s Belt & Road International Commercial Mediation Center to encourage mutual recognition of mediated settlements and arbitral awards. - Technology-Enabled ODR Platforms:

Develop online dispute resolution portals to handle cross-border investor disputes efficiently and cost-effectively.

3. Training and Certification of Mediators/Arbitrators

Capacity building is critical for credibility and investor trust.

- Accreditation Standards:

Adopt international benchmarks (IMI, CIArb, CEDR) for mediator and arbitrator accreditation. - Specialized Training Modules:

- International commercial arbitration (UNCITRAL Model Law, New York Convention).

- FIDIC contract dispute resolution (for infrastructure projects).

- Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) and ICSID procedures.

- Cross-cultural negotiation and mediation (especially for Chinese–Pakistani joint ventures).

- Continuous Professional Development (CPD):

- Require regular refresher courses and mock hearings to maintain competence.

- Panel Creation:

Maintain a roster of accredited mediators and arbitrators who are bilingual (English/Urdu/Mandarin) and trained in large-scale infrastructure and energy project disputes.

4. Institutional and Governmental Support

- Legislative Reform:

Amend Pakistan’s Arbitration Act to incorporate UNCITRAL Model Law provisions, ensuring neutrality and enforceability of awards. - Judicial Training:

Train judges in arbitration law to minimize judicial intervention and promote pro-enforcement policies. - Public–Private Partnerships:

Engage chambers of commerce, law firms, and academia to co-develop training curricula and case management protocols. - International Cooperation:

Sign cooperation agreements with SIAC, HKIAC, ICC, and CIETAC for knowledge-sharing, joint conferences, and panel exchanges.

5. Risk Mitigation and Investor Confidence

- Transparency: Publish anonymized awards and mediation outcomes to build trust and predictability.

- Funding Mechanisms: Explore third-party funding (TPF) options and cost-capping measures to ensure access to justice for smaller contractors.

- Belt & Road Legal Database: Maintain a database of past disputes, awards, and settlements to guide future project stakeholders and prevent repetitive claims.

III. Cross-Border Construction Disputes: A Framework for ADR and Arbitration under the Beltway/BRI Projects

1. Model Contract Clauses for Construction Disputes

a. Multi-Tier Dispute Resolution Clause

Adopt a step clause that integrates negotiation, mediation, and arbitration for construction contracts (FIDIC-based or bespoke):

- Negotiation: Senior representatives meet within 14–21 days of a dispute notice.

- Mediation: If negotiation fails, refer the dispute to institutional mediation (CIETAC Mediation Center, SIAC-SIMC Protocol, or a proposed Pakistan International Mediation Center).

- Arbitration: If mediation fails within a fixed period (e.g., 45 days), disputes proceed to final and binding arbitration under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules or ICC/CIETAC Construction Arbitration Rules.

b. Seat of Arbitration

- Neutral Venue: Singapore, Hong Kong, or Kuala Lumpur for cross-border projects.

- Domestic Option: Islamabad or Karachi, provided Pakistan updates its Arbitration Act to align with the UNCITRAL Model Law and ensures judicial non-interference.

c. Governing Law

- Hybrid Approach: Choose Pakistani substantive law for local construction compliance + internationally accepted procedural rules (UNCITRAL).

- For EPC/turnkey projects, consider English law or FIDIC-based contractual terms for predictability and uniform interpretation.

2. UNCITRAL Model Law Adoption and Harmonization

For Pakistan

- Legislative Reform: Modernize Pakistan’s Arbitration Act 1940 to fully incorporate UNCITRAL Model Law (as done by Singapore, Hong Kong, India).

- Recognition of Foreign Awards: Strengthen enforcement under the New York Convention by removing procedural hurdles and standardizing timelines.

For China

- Expand pilot programs for ad hoc arbitration and foreign-related disputes.

- Promote mutual enforcement agreements with Pakistan under the Belt & Road legal cooperation framework to streamline recognition of arbitral awards and mediated settlements.

3. Singapore Convention on Mediation (SCM) Integration

- Ratification and Implementation: Both China (signatory, not yet ratified) and Pakistan should ratify the Singapore Convention to allow cross-border enforcement of mediated settlements without the need for separate litigation.

- Regional Mediation Panels: Create a Joint China–Pakistan Construction Mediation Panel with experts in FIDIC contracts, PPP financing, and large infrastructure projects.

- Hybrid Med-Arb Mechanisms: Integrate mediation within arbitration proceedings (as allowed under Chinese law) to encourage settlement and reduce costs.

4. Development of Dispute Resolution Forums

National Centers

- Pakistan International Arbitration & Mediation Center (PIAMC): Dedicated hub for construction and infrastructure disputes with bilingual (English/Urdu) panels.

- Training Facilities: On-site mock arbitration rooms, mediation chambers, and digital case management systems.

Regional Cooperation

- Establish a Beltway Dispute Resolution Forum (BDRF) in collaboration with:

- CIETAC (China International Economic & Trade Arbitration Commission)

- SIAC (Singapore International Arbitration Centre)

- HKIAC (Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre)

- ICC International Court of Arbitration

- Develop a joint code of best practices and maintain a shared roster of accredited arbitrators/mediators.

5. Stakeholder Engagement

- Business & Chambers of Commerce: Regular ADR awareness sessions, contract drafting clinics, and dispute-prevention workshops.

- Government & Regulators: Ensure supportive legal frameworks and tax incentives for ADR participation.

- Financial Sector: Encourage banks, insurers, and multilateral lenders to require ADR clauses in project finance agreements.

- Lawyers’ Associations: Offer CIArb/IMI-accredited training programs and create panels of construction law specialists.

- Academia: Introduce construction arbitration and mediation courses in LL.M./LL.B and Business Law curricula, sponsor research on comparative dispute resolution.

6. Training and Certification of Neutrals

- Accreditation: Use CIArb Fellowship, IMI-certified mediation programs, and FIDIC adjudicator training.

- Cross-Cultural Skills: Include modules on Chinese business culture, negotiation psychology, and Belt & Road legal frameworks.

- CPD & Mock Hearings: Require annual participation in simulated arbitrations/mediations to maintain panel eligibility.

- Diversity: Promote inclusion of women professionals and young practitioners to expand the talent pool.

7. Regional and Multilateral Coordination

- Model Bilateral/Multilateral Treaties: Create a China–Pakistan–Central Asia–Middle East dispute resolution cooperation treaty covering recognition of arbitral awards, mediated settlements, and interim measures.

- Shared Case Law Database: Maintain a cross-border construction dispute jurisprudence repository accessible to practitioners and arbitrators in the region.

- Funding & Cost Allocation: Explore third-party funding (TPF) and capped costs regimes to make international arbitration affordable for local contractors.

Cross-Border Construction Dispute Resolution: Comparative Analysis and Recommendations

Comparative Table: Arbitration & ADR Frameworks in Regional Jurisdictions

| Jurisdiction | Arbitration Law | Model Law Adoption | Mediation / ADR Mechanisms | Enforcement of Awards | Unique Features / Challenges |

| China | Arbitration Law 1994 (Draft Amendment ongoing) | Partial (institutional arbitration only; ad hoc allowed in FTZ pilots) | People’s Mediation, Labor Dispute Arbitration, Med-Arb within proceedings | Party to New York Convention; SPC reporting mechanism ensures consistency | Court/tribunal-led mediation is prominent; enforcement delays possible |

| Pakistan | Arbitration Act 1940 (outdated) | No; needs UNCITRAL Model Law incorporation | Court-annexed mediation (Punjab ADR Act 2019); ad hoc arbitration common | NYC implementation weak but improving; enforcement can be delayed | Judicial intervention frequent; reforms in progress to modernize framework |

| Singapore | International Arbitration Act (UNCITRAL Model Law based) | Yes (fully aligned) | SIMC Mediation; Arb-Med-Arb Protocol | NYC signatory; very pro-enforcement judiciary | Global hub for arbitration; SIAC highly preferred by investors |

| Hong Kong | Arbitration Ordinance (UNCITRAL Model Law based) | Yes (fully aligned) | Court and institutional mediation; HKIAC-administered procedures | NYC signatory; very efficient enforcement | Strong confidentiality protections; ad hoc & institutional options available |

| India | Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 (amended 2015, 2019) | Yes (based on UNCITRAL Model Law) | Court-annexed mediation; commercial mediation bill pending | NYC signatory; enforcement improved after 2015 amendments | Judicial delays still common but slowly improving |

IV. Cross-Border Construction Dispute Resolution under Beltway/BRI Projects

Comparative Analysis

China’s Arbitration Law (1994) institutionalizes arbitration, with pilot programs allowing ad hoc arbitration in Free Trade Zones.

Mediation is widely encouraged, with mediators often being arbitrators in the same matter (med-arb). Pakistan, however, still operates under the Arbitration Act 1940,

which lacks UNCITRAL alignment and results in frequent judicial interference. Singapore and Hong Kong are fully aligned with the UNCITRAL Model Law, with strong pro-enforcement judicial policies, making them preferred seats for international construction arbitration.

UNCITRAL Model Law and Singapore Convention

Harmonization of Pakistan’s arbitration law with UNCITRAL Model Law would bring neutrality, predictability, and enforceability to awards.

Ratification of the Singapore Convention on Mediation by both China and Pakistan would enable cross-border enforcement of mediated settlements,

thereby encouraging amicable dispute resolution.

Recommendations

1. Model multi-tier clauses (negotiation → mediation → arbitration) for FIDIC contracts should be made mandatory in BRI projects.

2. Establishment of Pakistan International Arbitration and Mediation Center (PIAMC) with specialist panels on construction law.

3. Judicial training to reduce intervention and support speedy enforcement.

4. Regional collaboration with SIAC, HKIAC, CIETAC, and ICC for joint panels and capacity building.

5. Comprehensive mediator and arbitrator accreditation program (CIArb, IMI, CEDR standards) with modules on cross-cultural negotiation.

V. Model Multi-Tier Dispute Resolution Clause for Construction Contracts

The following model clause is drafted for FIDIC-based and other large construction contracts in the context of Beltway/BRI projects.

It is consistent with UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the New York Convention, and the Singapore Convention on Mediation.

Model Clause

1. Negotiation Phase

In the event of any dispute arising out of or in connection with this Contract, including any question regarding its existence, validity, or termination,

the parties shall first seek to resolve the dispute amicably through good faith negotiations between their senior executives within fourteen (14) days of a written notice of dispute.

2. Mediation Phase

If the dispute is not resolved within thirty (30) days after commencement of negotiations, the parties agree to refer the dispute to mediation administered by an

internationally recognized mediation institution such as the Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC), CIETAC Mediation Center, or a Pakistan International Mediation Center (PIAMC),

under its Mediation Rules in effect on the date of the request for mediation. The mediation shall be conducted in English, and if a settlement is reached, the settlement agreement shall be binding and enforceable under the Singapore Convention on Mediation (if ratified).

3. Arbitration Phase

If the dispute has not been settled by mediation within forty-five (45) days from the commencement of mediation, the dispute shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration

administered by the chosen arbitral institution (ICC, SIAC, HKIAC, or CIETAC) in accordance with its arbitration rules in effect at the time of the notice of arbitration,

which rules are deemed to be incorporated by reference into this clause. The seat of arbitration shall be [Singapore/Hong Kong/Islamabad], the language of arbitration shall be English,

and the governing law shall be [Pakistani law or other agreed governing law]. The arbitral award shall be final and binding on the parties and enforceable under the New York Convention.

4. Interim Measures and Consolidation

The arbitral tribunal shall have power to order interim measures and to consolidate proceedings or join additional parties, subject to the consent of the parties, to ensure efficient resolution of multi-contract disputes.

This model clause is designed to promote dispute avoidance and early settlement, while preserving the parties’ right to final and binding arbitration. It is compatible with FIDIC dispute resolution mechanisms and can be adapted for PPP, EPC, and turnkey contracts. The explicit reference to the Singapore Convention ensures cross-border enforceability of mediated settlements, thereby reducing enforcement risk.

Conclusion

China has made notable progress in developing its arbitration and ADR mechanisms but must further strengthen party autonomy, judicial consistency, and international integration to compete with global arbitration hubs. For Pakistan, the success of Beltway and BRI projects relies on creating a predictable, investor-friendly dispute resolution system. By adopting UNCITRAL-aligned arbitration laws, ratifying the Singapore Convention, establishing modern ADR centers, and training mediators and arbitrators, both China and Pakistan can turn dispute resolution into a competitive advantage. Coordinated efforts by governments, business chambers, financiers, lawyers, and academia will position Pakistan as a regional hub for cross-border construction dispute resolution, boosting investor confidence and ensuring efficient, sustainable infrastructure development.

References

- See Article 48 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024).

- See Article 50 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024).

- See Article 41 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024).

- See Article 26 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024).

- See Article 27 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024).

- See Article 86 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules (2024)

- See https://www.bjac.org.cn/news/view?id=4989

- “International awards” refer to the awards made outside China. If the 2024 Draft takes effect, “international awards” will refer to the awards with foreign arbitration seats.

- See Article 248 of the Civil Procedure Law.

- See Article 291 of the Civil Procedure Law.

- See Article 77 of the 2021 Draft.

- See Article 68 of the 2024 Draft.

- A foreign-related civil relation may be identified by a People’s Court if: (1) one of the parties concerned or both parties concerned are foreign citizens, foreign legal persons or other organisations or stateless persons; (2) the habitual residence of one of the parties concerned or of both parties concerned is outside the territory of the PRC; (3) the subject matter is outside the territory of the PRC; (4) the legal fact that causes the civil relation to create, change or terminate occurs outside the territory of the PRC; or (5) there is any other circumstance which can be identified as a foreign-related civil relation.

- Arbitration Law of the People’s Republic of China 1994 (PRC).

- UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration 1985, with amendments as adopted in 2006.

- New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 1958.

- Singapore Convention on Mediation 2019 (United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation).

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 (India).

- International Arbitration Act (Singapore).

- Arbitration Ordinance (Hong Kong).

- Punjab ADR Act 2019 (Pakistan).