The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID): A Critical Appraisal of its Legitimacy, Effectiveness, and Future Trajectory

Mian Zafar Iqbal Kalanauri,

Advocate Supreme Court Pakistan, Arbitrator (Fellow CIArb), Barrister, Mediator (CEDAR, IMI, CMC, USA), Master Trainer in Mediation (CEDAR), Legal Educator, Reformist of Judicial System and Legal Education, White-Collar Crime Investigator

Abstract

The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) was established in 1966 to promote international investment by providing a stable and unbiased forum for resolving investor-State disputes. While ICSID is widely recognized as the leading institution for investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS), it has faced increasing scrutiny regarding its legitimacy, fairness, and transparency. This article critically examines the role of ICSID within the broader framework of international investment law. It evaluates the key advantages and disadvantages of the ICSID system for both investors and host States, explores notable cases that highlight systemic issues, and proposes practical suggestions for reform. Through a multi-faceted analysis, this paper assesses ICSID’s historical contributions and its ongoing struggle to balance investor protection with public interest concerns, particularly those of developing host states. The Pakistani perspective, with reference to landmark cases such as Reko Diq, SGS v. Pakistan, and Bayindir, is specifically examined to illustrate the systemic challenges faced by developing countries.

1. Introduction

After World War II, global investment increased, creating a need for a neutral and reliable mechanism to settle disputes between sovereign states and private foreign investors. ICSID was created under the auspices of the World Bank to fill this need, thereby removing investment disputes from diplomatic protection. This article moves beyond a descriptive account of ICSID to provide a critical, academic analysis. It dissects the institutional and procedural elements of ICSID arbitration and evaluates the extent to which it has fulfilled its founding mandate while addressing the valid critiques leveled against it.

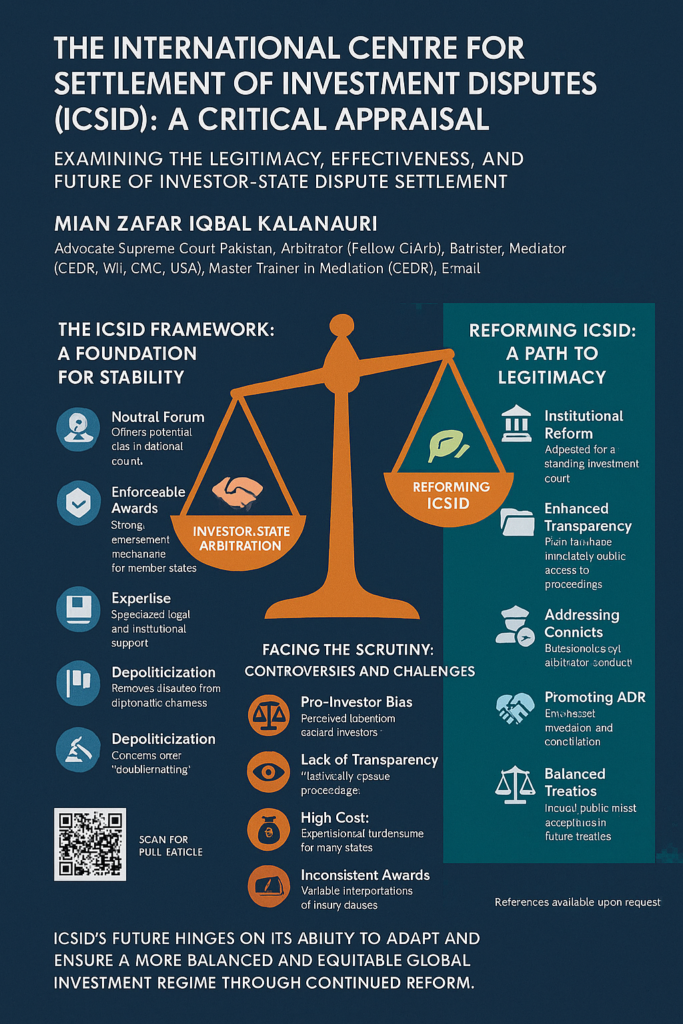

2. Advantages of the ICSID Framework

ICSID offers several distinct advantages that have made it the most widely utilized forum for investor–State dispute settlement (ISDS).

- Neutral and Independent Forum: By removing disputes from domestic courts of host states, ICSID assures foreign investors that adjudication will be impartial. This neutrality is particularly significant in developing countries, where concerns about judicial independence or inefficiency often prevail.¹

- Enforceability of Awards: ICSID awards are enforceable in all 158 Contracting States without the need for domestic recognition procedures, as required under the New York Convention.² Enforcement is automatic and insulated from local judicial review, enhancing legal certainty for investors.³

- Institutional Expertise: ICSID provides specialized administrative support, experienced arbitrators, and a consistent procedural framework. Its Secretariat offers technical assistance, while its case law contributes to shaping international investment jurisprudence.⁴

- Depoliticization of Disputes: By channeling disputes into a legal rather than diplomatic framework, ICSID reduces the likelihood of inter-state political tensions and investor reliance on diplomatic protection.⁵

- Predictability and Legal Certainty: The ICSID Convention and Arbitration Rules create procedural clarity, while its growing body of case law provides guidance for states and investors, fostering stable expectations and promoting foreign direct investment (FDI).⁶

3. Disadvantages and Criticisms of ICSID

Despite its contributions, ICSID has been subject to persistent criticism, particularly from host states in the Global South.

- Perceived Pro-Investor Bias: Scholars argue that ICSID jurisprudence tends to favor investors, interpreting treaty protections such as “fair and equitable treatment” broadly, often at the expense of host state regulatory autonomy.⁷ This has raised legitimacy concerns.

- Lack of Transparency: Historically, proceedings and awards were confidential unless parties consented to publication. Although reforms in the 2022 ICSID Rules mandate disclosure of third-party funding and encourage publication, critics argue that opacity persists.⁸

- High Costs: ICSID arbitration is often prohibitively expensive. Tribunal fees, expert witness costs, and legal representation can run into tens of millions of dollars, straining state budgets.⁹

- Inconsistency in Awards: Unlike common law courts, ICSID tribunals are not bound by stare decisis. Inconsistent interpretations of key standards, such as indirect expropriation or legitimate expectations, have undermined predictability.¹⁰

- Arbitrator Conflicts of Interest (“Double-Hatting”): Arbitrators often serve as counsel in other investment disputes, raising questions of impartiality.¹¹ The 2022 reforms attempt to limit these practices, but critics argue enforcement mechanisms remain weak.

4. Notable Cases and Illustrative Controversies

Several landmark ICSID cases underscore the tensions between investment protection and state sovereignty:

- Metalclad Corporation v. Mexico (ICSID Case No ARB(AF)/97/1): The tribunal found that Mexico’s refusal to grant a construction permit for environmental reasons amounted to indirect expropriation.¹² This case is often cited as evidence of ICSID’s expansive interpretation of investor rights, with potential chilling effects on environmental regulation.

- Argentina’s Emergency Measures Cases (CMS v. Argentina, Enron v. Argentina, Sempra v. Argentina): Following Argentina’s 2001 economic crisis, tribunals inconsistently interpreted treaty provisions on necessity and emergency measures.¹³ Some claims were upheld, others dismissed, revealing a lack of coherence and predictability in ICSID jurisprudence.

- Philip Morris v. Uruguay (ICSID Case No ARB/10/7): Tobacco giant Philip Morris challenged Uruguay’s anti-smoking regulations as a violation of investment treaty protections. Although Uruguay prevailed, the case demonstrated how ISDS can be used to contest public health measures, imposing significant litigation costs on states.¹⁴

These cases illustrate the core legitimacy concerns surrounding ICSID: investor protections can undermine a state’s sovereign right to regulate in the public interest, with broader implications for democracy, health, and environmental policy.

Pakistan and ICSID: Lessons from a Developing State

4A. Pakistan’s Engagement with ICSID

Pakistan has had a complex relationship with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), shaped by its extensive bilateral investment treaty (BIT) network and a series of high-profile disputes. As one of the earliest signatories to the ICSID Convention (1965), Pakistan sought to attract foreign investment by offering investors a neutral forum for dispute resolution. However, the country’s subsequent experience reflects both the opportunities and vulnerabilities of developing states within the ICSID framework.

Key ICSID Cases Involving Pakistan

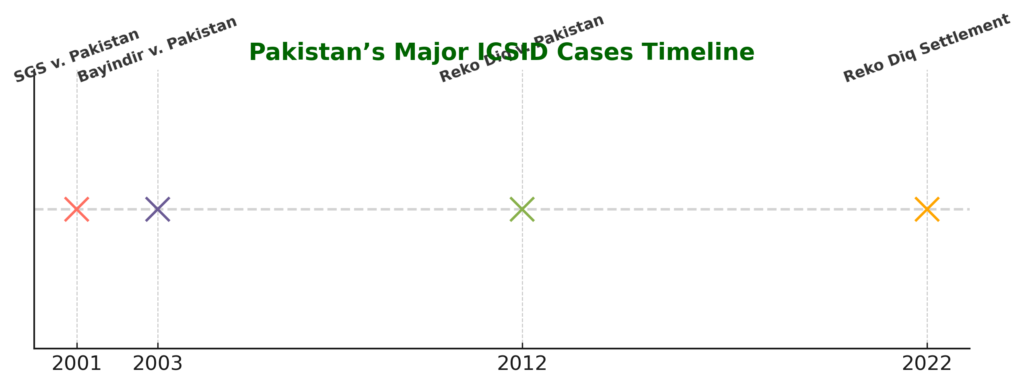

- SGS Société Générale de Surveillance v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No ARB/01/13)

This early claim concerned contractual obligations under the Pakistan–Switzerland BIT. The tribunal’s expansive interpretation of “investment” and its jurisdictional findings highlighted the broad reach of ICSID jurisdiction. The case sparked domestic debate about Pakistan’s exposure to international arbitration even for commercial disputes that could otherwise be resolved in local courts.¹ - Bayindir Insaat Turizm Ticaret Ve Sanayi A.S. v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No ARB/03/29)

The dispute arose from a highway construction project. The tribunal considered claims of expropriation and denial of fair and equitable treatment (FET). While Pakistan prevailed in part, the tribunal scrutinized governmental decisions in infrastructure development, raising concerns about how ICSID tribunals assess state regulatory discretion.² - Tethyan Copper Company Pty Ltd v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No ARB/12/1)

The Reko Diq case represents one of the most consequential ICSID awards in history. Pakistan was ordered to pay USD 5.9 billion for denying a mining lease to the investor.³ The award equaled nearly 2% of Pakistan’s GDP, underscoring the financial vulnerability of developing states. Although Pakistan negotiated a settlement in 2022, the case exposed deep tensions between domestic constitutional law (Reko Diq Case, PLD 2013 SC 641) and international investment law obligations.⁴

4B. Policy Concerns and Critiques

Pakistan’s ICSID experience illustrates structural challenges that resonate with broader critiques of the ISDS system:

- Regulatory Space and Sovereignty: Cases like Reko Diq reveal how domestic regulatory measures (including constitutional judgments by the Supreme Court of Pakistan) may trigger massive liability under ICSID arbitration.⁵

- BIT Overexposure: Pakistan has signed more than 50 BITs, many containing vague provisions on FET and expropriation. These treaties, often negotiated in the 1990s without adequate safeguards, have left Pakistan highly exposed to claims.⁶

- Cost and Resource Strain: Defending ICSID claims has imposed significant fiscal and institutional burdens. Legal fees in Reko Diq exceeded USD 60 million, highlighting the disproportionate costs borne by developing countries.⁷

- Legitimacy and Public Perception: High-value awards have fueled domestic criticism that ICSID unduly favors investors and undermines Pakistan’s democratic and constitutional order.⁸

4C. Reform Initiatives in Pakistan

In light of these challenges, Pakistan has begun reassessing its international investment law strategy:

- BIT Review and Renegotiation: Pakistan has initiated a review of its BIT program to incorporate safeguards such as exhaustion of local remedies, tighter definitions of “investment,” and explicit recognition of state regulatory powers in areas like environment, health, and natural resources.⁹

- Comparative Learning from South Asia: Drawing lessons from India’s 2016 Model BIT, Pakistan is considering provisions that limit investor rights while emphasizing sustainable development goals.¹⁰

- Strengthening Domestic Legal Infrastructure: There are calls within Pakistan’s legal community for the creation of specialized investment law divisions within domestic courts, which could provide credible local alternatives and reduce reliance on ICSID.¹¹

- Embracing ADR and Mediation: The Punjab ADR Act 2019 and emerging national mediation frameworks provide opportunities for resolving investor-state disputes through less adversarial mechanisms, potentially integrated with ICSID’s conciliation and mediation services.¹²

4D. Pakistan’s Experience as a Lens for ICSID Reform

Pakistan’s turbulent journey through ICSID arbitration exemplifies the systemic concerns facing developing states. The financial and sovereignty costs borne in cases like Reko Diq underscore the need for reforms such as:

- clearer treaty drafting,

- enhanced transparency,

- accessible alternatives to arbitration, and

- a rebalancing of the ISDS system to ensure host states’ right to regulate is not subordinated to investor interests.

By situating Pakistan’s case studies within the global ICSID reform debate, it becomes evident that the institution’s future legitimacy depends on addressing the asymmetries exposed by such disputes. Pakistan’s experience thus provides both a cautionary tale and a potential roadmap for reconciling investment protection with public interest imperatives.

5. Suggestions for Reform and Improvement

Reforms proposed include creating a standing investment court, enhancing transparency, addressing arbitrator conflicts of interest, promoting ADR such as mediation, and clarifying treaty provisions. From Pakistan’s perspective, reforms must ensure balance between investment promotion and sovereign regulatory space. Lessons can be drawn from India’s 2016 Model BIT, which emphasizes public interest safeguards.

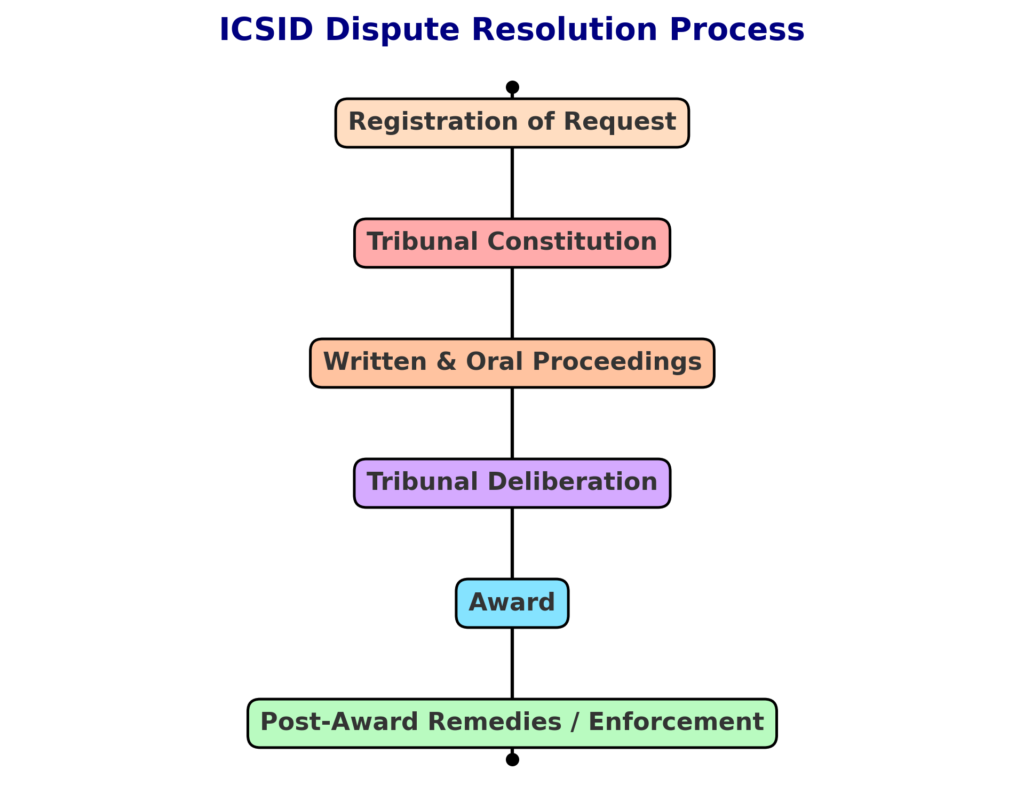

6. Visual Flowcharts and Diagrams

To complement the analysis, the following diagrams provide a visual representation of ICSID processes, Pakistan’s experience, and reform proposals.

Pakistan’s Major ICSID cases Timeline

6. Conclusion

ICSID has played a pivotal role in international investment law, but it faces a crisis of legitimacy. The Pakistani experience demonstrates how ICSID can impose significant financial and constitutional pressures on developing countries. The future of ICSID depends on evolving into a balanced system that respects both investor rights and host state sovereignty.

References:

- Christoph Schreuer et al, The ICSID Convention: A Commentary (2nd edn, CUP 2009) 83.

- ICSID Convention 1965, art 54.

- Emmanuel Gaillard, ‘Enforcement of ICSID Awards’ (2001) 18(1) ICSID Review 1.

- Meg Kinnear, ‘ICSID at Fifty’ (2016) 31(2) ICSID Review 409.

- Aron Broches, ‘The Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes: Some Observations on Jurisdiction’ (1972) 5(2) Columbia J Transnat’l L 263.

- UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2023 (United Nations 2023).

- Gus Van Harten, Investment Treaty Arbitration and Public Law (OUP 2007).

- ICSID, 2022 Rules Amendment: Fact Sheet (World Bank, 2022).

- Susan Franck, ‘Rationalizing Costs in Investment Treaty Arbitration’ (2011) 88(3) Washington Univ L Rev 769.

- Stephan Schill, ‘Consistency in ICSID Jurisprudence’ (2010) 17(1) ICSID Review 87.

- Catherine Rogers, ‘The Ethics of Arbitrators’ (2014) 3 Global Arb Rev 16.

- Metalclad Corporation v Mexico, ICSID Case No ARB(AF)/97/1, Award (30 August 2000).

- CMS Gas Transmission Company v Argentina, ICSID Case No ARB/01/8, Award (12 May 2005); Enron Corporation v Argentina, ICSID Case No ARB/01/3, Award (22 May 2007); Sempra Energy v Argentina, ICSID Case No ARB/02/16, Award (28 September 2007).

- Philip Morris Brands Sàrl v Uruguay, ICSID Case No ARB/10/7, Award (8 July 2016).

- SGS Société Générale de Surveillance v Islamic Republic of Pakistan, ICSID Case No ARB/01/13, Decision on Jurisdiction (6 August 2003).

- Bayindir Insaat Turizm Ticaret Ve Sanayi A.S. v Islamic Republic of Pakistan, ICSID Case No ARB/03/29, Award (27 August 2009).

- Tethyan Copper Company Pty Ltd v Islamic Republic of Pakistan, ICSID Case No ARB/12/1, Award (12 July 2019).

- Maulvi Abdul Haq Baloch v Federation of Pakistan (Reko Diq Case) [2013] PLD SC 641.

- Moeen H Cheema, ‘Investment Arbitration and Constitutional Supremacy: Lessons from Reko Diq’ (2014) LUMS LJ 1.

- UNCTAD, Pakistan Bilateral Investment Treaties Database https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org accessed 7 September 2025.

- Luke Eric Peterson, ‘Pakistan Faces Costs of Over $60m in Reko Diq Arbitration’ IA Reporter (2020).

- Shahid Kardar, ‘Reko Diq: International Arbitration and Pakistan’s Vulnerability’ Dawn (Karachi, 21 July 2019).

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of Pakistan, Report on Bilateral Investment Treaties Review (2021).

- Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Model Text for the Indian Bilateral Investment Treaty (2016).

- Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, ‘Strengthening Investment Arbitration in Pakistan: The Case for Specialized Divisions’ (2020) Pakistan Journal of International Law 33.

- Punjab ADR Act 2019 (Act XX of 2019).